In the café where we met in February 1986, on the day I arrived in Japan, you wrote ‘Iwama made kudasaï’ in Japanese on a piece of paper and handed it to me in case I got lost between Tokyo and the small village of Iwama. It was just a few words, ‘to Iwama, please,’ but that day I was happy to be able to fold that piece of paper in my pocket, as if it were a safe-conduct pass.

For taking the time to do that when we were still strangers to each other, much obliged Stan.

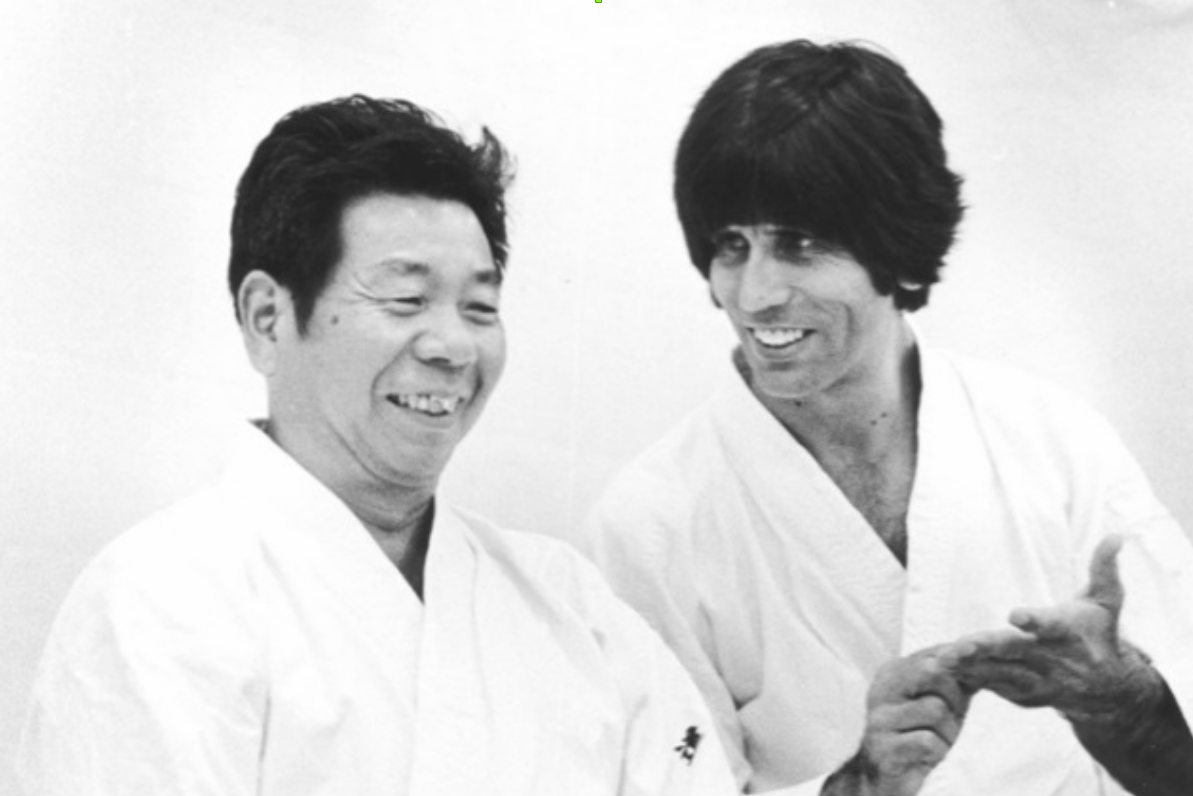

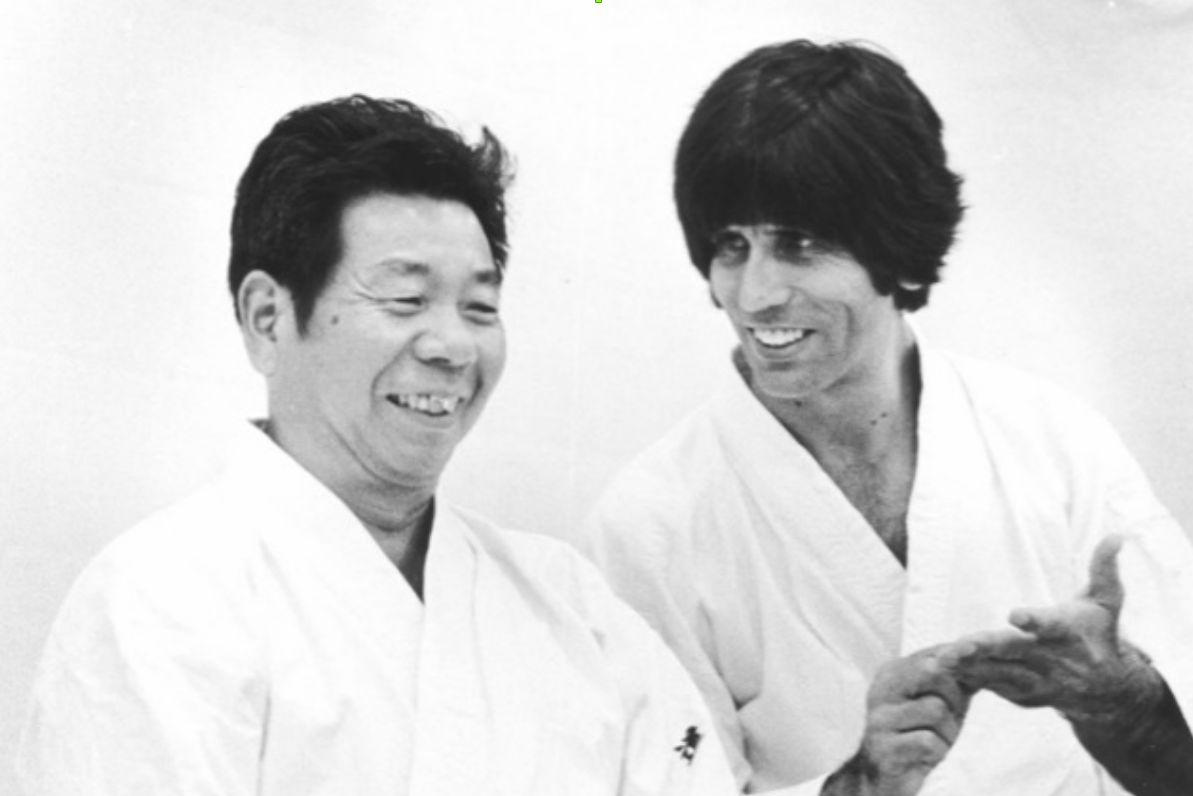

In the late 1980s, you used to come from Tokyo every week to study under Master Saito in the old dojo in Iwama. After class, it was a pleasure and a privilege to hear your anecdotes and stories about your discoveries in the history of Aikido:

You unearthed the first treasure in 1979, in the archives of a film library in Tokyo: the 16 mm film of O Sensei shot in 1935 in Osaka, at the Asahi Shinbun, formal proof that the art known today as Aikido had already reached an advanced stage of development at that time, long before the name Aikido was even established. You had asked the staff to show you some reels that were gathering dust on a shelf, and suddenly O Sensei appeared on the screen, in what is undoubtedly one of his most beautiful and longest demonstrations.

For bringing such a marvel out of oblivion, much obliged Stan.

If only one name were to be mentioned among the personalities who enabled the development of Aikido in its early days, it would be that of Admiral Isamu Takeshita. A major figure in the Russo-Japanese War, he was an enthusiastic student of Morihei Ueshiba and introduced his teacher to Yamamoto Gonnohyoe, former Prime Minister of Japan. This is how Ueshiba obtained the position of instructor in Japan's military and police academies.

It was also Admiral Takeshita who first introduced Aikido to the United States, initiating President Theodore Roosevelt himself in the White House during the diplomatic talks that ended the Russo-Japanese War. For his essential role in these talks, Takeshita received his country's highest honour, the Order of the Rising Sun.

Finally, it was Isamu Takeshita who conceived and organised O Sensei's Aikido demonstration at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo in 1941, in front of the assembled court and imperial family, an event that gave Aikido its letters of nobility.

I can imagine your emotion, Stan, on the day you got your hands on the boxes filled with notes written by this exceptional figure: hundreds of densely written pages, carefully and intelligently recording the content of O Sensei's daily lessons between 1925 and 1940, during which time Takeshita was a diligent practitioner, despite his advanced age.

And I remember you grumbling about Master Saito because he never bothered to really read the notes you gave him to study and compare with the lessons he himself had received from O Sensei. What an edifying lesson could have come from that comparison! It's a shame, of course, but one day someone will work on this testimony and draw from it the riches it contains for the knowledge of Aikido. The work of this future researcher will be made possible by the care you took to preserve these documents.

And for the trails of this kind that you left open for the future, much obliged Stan.

Among all your surprises, the most beautiful undoubtedly came from Zenzaburo Akazawa, a citizen of Iwama and famous student of O Sensei in the 1930s. In the middle of an interview you were conducting with him, Zenzaburo left for a moment. He returned, to support his words, with a book known to only a few people: the only book ever written by Morihei Ueshiba, published privately in 1938 for Prince Kaya Tsunenori, first cousin of the Empress of Japan, and then offered as a token of gratitude to those who had helped O Sensei develop Aikido.

Until you held this priceless work on the thoughts and techniques of the founder of Aikido in your hands for the first time, the whole world was unaware of its existence.

‘Budo’ had a profound effect on you; O Sensei's book changed your perception of Aikido. Indeed, as great as your admiration for Master Saito was at the time, you were not convinced that the techniques he taught in Iwama were a faithful reflection of the Founder's teaching. But reading the little book swept away your doubts; it was clearly the same teaching, gesture for gesture, word for word, explanation for explanation. And you were the first to reach this revolutionary conclusion: if there is no difference between the Aikido taught by O Sensei to Saito from 1946 to 1969 and the Aikido of 1938 (and even earlier, as the 1935 film gives sufficient credence to the idea) then, despite popular belief, the modern evolution of Aikido is an event that cannot be attributed to the Founder. This evolution is therefore necessarily linked to the teaching given at the Aikikai. In other words, the practice of the Aikikai, presented throughout the world as the ultimate guarantee of authenticity, has in fact deviated from the Founder's teaching, making those who have remained faithful to it appear deviant by comparison.

You understood this before anyone else, and you began to make it known. In your enthusiasm, you personally organised a reprint of Budo in Japanese and presented the first copy to Master Saito. You could hardly believe it when he told you that he was seeing the book for the first time, even though he had shared the Founder's daily life for 23 years. It is not every day that one experiences such joy, and of the countless gifts he received in his life, this was by far the most beautiful. Thanks to you, he was able to travel the world for many years with this little book under his arm, demonstrating at every seminar how his teaching was a faithful reflection of O Sensei's teaching, contrary to what the global development of Aikido under the Aikikai might have led one to believe.

So for him, who would not have been quite the same person if he had not found this book one day on his path, much obliged Stan.

Sadly, while I was visiting you in Tokyo in 1987, you confessed your disappointment to me, pointing to a pile of boxes at the back of a room. Kisshomaru Doshu, O Sensei's son, would not allow the book to be published. So, as we closed the door to go and eat soba at the corner of the street, you took a copy from one of the boxes and handed it to me with a friendly gesture. It was a wonderful gift for me, long before the first English translation of this book by John Stevens. I had no idea at the time how important this document would be for my development in Aikido in the decades that followed, and to this day.

For this gesture of friendship, which had such an impact on me, much obliged Stan.

In 1989, I invited Master Saito to France. You requested that I purchase plane tickets for you and your wife, as you had just gotten married and this was an opportunity to add a honeymoon to the Aikido tour. It was with regret that I had to cancel the tickets at the last minute, as Master Saito had decided that you would not be the translator this time. I still have a few copies of the Aiki News magazines you sent me at the time for the tour, tucked away in a desk drawer.

For this magazine too, and the wealth of information it represented from the 1970s onwards for a whole generation before the internet, much obliged Stan.

The things of a lifetime, my old friend. Now that you have decided to seek your sources from O Sensei himself, those who have benefited over the last forty years from your research into the origins of Aikido have lost a friend with remarkable intuition and strength of labour.

The men and women who knew you will thank you in their own way. As for me, I express my gratitude here, but I would also like to say to the generations who will use your discoveries in the future, without necessarily knowing their origin, that they owe a debt of gratitude, beyond time, to Stanley Pranin.

Philippe Voarino, Chléire island, at the dawn of spring 2017

Stanley Pranin died on 7 March 2017.